EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Limited is a Swiss company with registered seats in Switzerland providing services to clients in Switzerland.

The European Union’s AI Act is set to become law soon. What does it mean for you and what steps do you need to take now?

In brief

- The EU AI Act will make huge demands on companies. That’s why it’s important to start preparing now.

- The key steps are to gain an understanding of the AI solutions you are using and implement an AI management system.

- To achieve this, clear lines of responsibility need to be established and different departments such as IT, legal, compliance and data protection need to work together.

The AI Act is a response to the growing and currently almost unregulated use of artificial intelligence. The brouhaha surrounding the release of ChatGPT, for example, and subsequent calls for at least a temporary moratorium on research into AI until the technology is better regulated, underscores the relevance of the proposed legislation. The aim of the AI Act is to ensure AI is used responsibly and is focused on the benefit to humanity, while not preventing further technical progress.

What is the AI Act?

As a directive, it must be implemented by all EU member states. Most of the provisions will apply 24 months after it enters into force. With the completion of the trilogue on 8 December 2023, the European Council, European Commission and European Parliament reached agreement on the main points of the AI Act. The final draft was agreed upon on 13 March 2024, and will enter into force 20 days after its publication – which is expected to be at the end of May 2024. Thereafter, the first rules banning certain AI systems will enter into force only six months later.

What is the AI Act about?

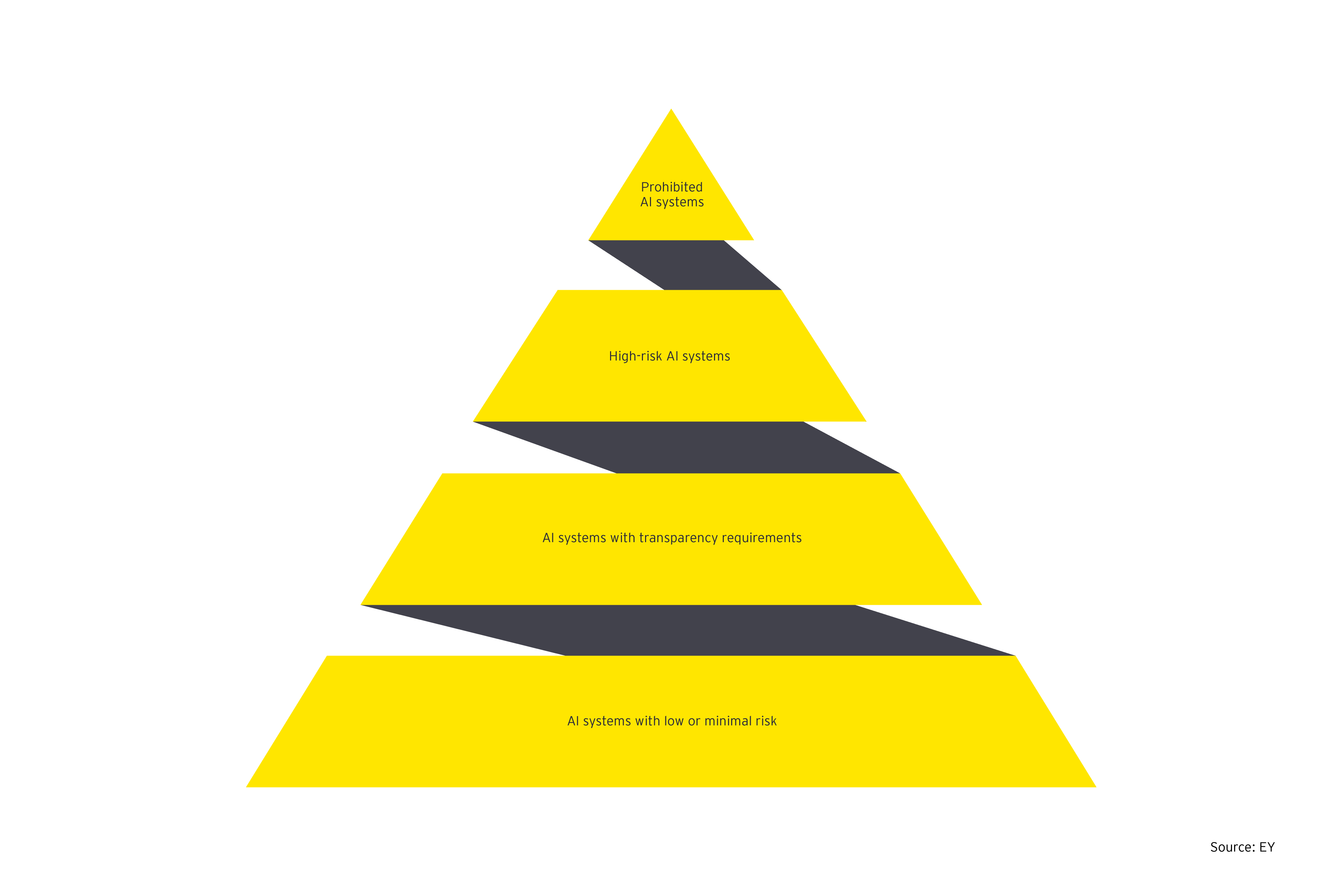

The AI Act takes a risk-based approach to regulating AI. AI systems are classified in different risk categories based on criteria such as their field of application and target group. The Act then defines measures to be implemented by companies that use or sell AI systems depending on the risk category. The required measures range from a simple disclosure obligation for low-risk applications (e.g. chatbots in customer service) to a wide-ranging documentation obligation and duty of care for high-risk applications (e.g. applications used in human resources) through to a complete ban on prohibited applications or applications that pose an unacceptable risk (e.g. social scoring or systems that seek to subliminally manipulate the behavior of children or people with intellectual disabilities).

As the above examples show, AI may not just be used in technical departments, but throughout the whole company. Clear lines of responsibility, inventory lists and risk assessments are still rare. However, these will be needed at the latest when the Act enters into force, as drastic fines can be imposed if the rules are breached. The maximum fine is set at 7% of a company’s entire global revenues in the previous year or 35 million euro. This is actually even higher than the potential fines under the GDPR, which are a maximum of 4% of revenues or 20 million euro. So how should companies prepare for the new law?

In a first step, stakeholders with AI responsibilities need to familiarize themselves with the principles, requirements and consequences of the AI Act. Management should be informed of the new legislation.

Ready for the AI Act? A road map

Before the AI Act enters into force: understand, review, plan

In a first step, stakeholders with AI responsibilities need to familiarize themselves with the principles, requirements and consequences of the AI Act. Management should be informed of the new legislation, as it needs to lay down clear lines of responsibility for implementing the requirements of the Act. This process may not be straightforward, as there may be a number of different functions within the company that could be given responsibility. If it is impossible to assign clear responsibilities, a committee should be formed of these functions to coordinate implementation and report to management. The relevant stakeholders are as follows:

- Chief Technology Officer (CTO): The IT or technology department is the obvious first port of call for digital issues such as AI. However, meeting legal requirements by means of a management system based on principles, measures, controls and documentation requirements is typically not among its core competences.

- General Counsel Office (GCO): As the AI Act involves statutory requirements, the legal department is also a possible option for locating the responsibility for meeting the requirements of the Act. However, technical expertise and, again, maintaining a comprehensive management system are not among the legal department’s classic responsibilities.

- Chief Compliance Officer (CCO): Many elements of an AI management system are already in place in the compliance area through the compliance management system (CMS). Moreover, the CMS means the compliance department has established channels to communicate with a range of other departments. It is also familiar with issues such as risk classification, deciding on measures to take and documenting them. Moreover the requirements of the AI Act can usually be integrated in an existing standard process of risk analysis and evaluation. Since the introduction of the GDPR, the compliance department usually also has a certain amount of technical expertise, which is needed for the AI Act.

- Data Protection Officer (DPO): Alongside the compliance department, the data protection function is also a suitable department to be given responsibility for the AI Act, particularly if it is expanded into a comprehensive data governance function which, in addition to simply protecting data, also considers its use, the legal compliance of the IT landscape and the associated risks. In addition, the data protection function is usually the interface between the CTO, GCO and CCO, irrespective of where it sits in the company’s organization. It could therefore make sense to hand responsibility for the AI Act to the DPO, provided it is an independent department, and give this department additional resources to fulfill a comprehensive governance function. Otherwise, conferring responsibility for the issue on a CCO looks the most viable option.

In addition to these functions, persons with detailed technical and legal expertise about AI from operating departments or middle management should be included in the committee to ensure it can answer detailed questions efficiently. Moreover, the current situation within the company such as existing responsibilities for related issues, any potential AI and/or innovation strategy, the areas where AI is used in the company and the existing regulatory framework need to be taken into account. These and other factors may of course influence the assessment as to how best to organize the lines of responsibility.

In addition to defining lines of responsibility, a clear timetable of measures implementing the requirements of the AI Act should also be set out based on a gap analysis. This gap analysis should also take account of the suitability of processes and guidelines, current staff training, a comprehensive record of the AI solutions that have been implemented (e.g. by means of an AI inventory) plus a number of further points which we will discuss below.

After the adoption of the AI Act, there will be a period of two years in which to meet the requirements. The timetable of measures will have to be implemented within this period.

During the transitional phase: implement, revise, prepare

After the adoption of the AI Act, there will be a period of two years in which to meet the requirements. The timetable of measures will have to be implemented within this period. The company needs to constantly review whether the milestones are being reached within the timetable.

Step 1: Inventory – Survey of what is currently in use

If the company doesn’t already have one, a comprehensive inventory of AI-related software, applications, algorithms and solutions used in the company should be produced. If available, the software asset management system within a company’s IT can be used to produce this. The installed software and associated licenses for all devices within a company are usually managed in this system.

The software asset management system can check every installed software program and determine whether it is using AI functionality or could potentially be used to implement AI. Instead of comparing manually, this can obviously also be done via data analysis of software databases and lists. In cases of doubt, your starting assumption should be that if a software offers the potential for AI, this functionality will be used, or indeed that AI has been implemented with this software.

This assumption should be verified and detailed by means of surveys/questionnaires and random checks. As the range of possible software and their functionalities is very large, the design and evaluation of the surveys should be performed by experts who may already have a list of possible AI functionality by software program and are able to assess the potential of the relevant software at a technical level.

If an asset management system is not available, a broader survey can be carried out in the company via questionnaires to establish whether AI-capable software is being used. Apart from the size of the survey, this should not affect how the survey is carried out. However, in a broad survey the initial response rate is usually much lower than when the survey participants are limited based on installed software solutions. Therefore, the management resources required for such a survey are significantly higher.

Irrespective of the specific form of the survey, it should always be designed in such a way that at the end all the required information about the software used in the company is available to carry out the risk classification described below and demonstrate this in the event of inquiries by the authorities.

Based on this initial classification and the resulting grouping into AI solutions and non-AI solutions, programs should then be classified into the risk categories of the AI Act.

Step 2: Classification into risk categories and determining requirements

Based on this initial classification and the resulting grouping into AI solutions and non-AI solutions, programs should then be classified into the risk categories of the AI Act. The requirements of the AI Act that need to be implemented flow from this. Subsequently, the measures in place in the company can be evaluated to ensure the compliance management system conforms to the requirements of the Act. Any gaps that are identified must be closed before the Act enters into force.

Risk categories and requirements

The definition of terms and risk categories was a major area of debate when the draft legislation was being prepared. The latest version of the Act has a definition of terms and risk categories in the annex. For example, the legislation uses the OECD’s definition of AI.

AI systems that are seen as a clear threat to EU citizens or jeopardize the health, safety or fundamental rights of people in a way that is disproportionate to the intended purpose are prohibited altogether by the AI Act. This includes, for example, social scoring by state bodies and systems attempting to predict people’s behavior for law enforcement purposes (“predictive policing”).

Only the following three of the risk categories listed in the AI Act are probably relevant for most companies’ day-to-day business:

High-risk AI systems are systems that pose risks to people’s health, safety or fundamental rights. The areas of use and specific purposes that this comprises are listed in the annex to the legislation and will be updated continuously after it enters into force. At the moment, this list comprises employment, HR management and access to self-employment (e.g. to select applicants, decide on promotions or check the performance and behavior of employees), management and operation of critical infrastructure (e.g. to manage electricity networks or rail traffic) and law enforcement, migration and asylum (e.g. to simplify decisions). Biometric monitoring of people also falls into the high-risk category. An AI system is also high risk if it falls under EU harmonized safety standards for which a conformity assessment procedure (i.e. an assessment and confirmation/certification) is required. Standards applying to machinery, medical devices, toys and elevators fall into this category.

There are extensive requirements set out in the AI Act for these high-risk systems:

1. Risk management

A risk management system to identify, assess and reduce risks must be put in place and applied to the AI systems.

2. Data quality

There are certain requirements for the data used for training, testing and validation. For example, this data must be relevant, representative, free of errors and complete.

3. Documentation

There must be automatically generated logs of the operations and comprehensive technical documentation.

4. Transparency and information requirements

There are particular requirements for transparency and information with respect to users. These are defined in greater detail in the annex to the Act. In addition, humans must be able to oversee the AI system and intervene in its operations, if necessary.

5. Technical requirements

Certain requirements relating to IT security must be met. There must be an appropriate degree of accuracy and robustness. Here too, the exact requirements are defined in more detail in the annex to the AI Act.

Those operating the AI solution are primarily responsible for ensuring that the requirements are complied with. They are responsible for evaluating compliance with the requirements and ensuring the AI is monitored by a human being. In addition, high-risk AI systems must be registered in an EU database. After the system has gone into use, the operator continues to be responsible for monitoring the AI systems and reporting incidents to the relevant authorities.

AI systems with transparency requirements are systems that interact with people, carry out emotion recognition or biometric classification, or generate artificial content that mimics real people, places or objects (“deep fakes”). This content must be specially identified so that users are aware they are using AI and to prevent illegal content from being produced.

Low-risk AI systems are defined as those that are not expected to pose any risk to users or their data, for example, AI solutions used in sandboxes for testing purposes. The requirements of general product safety apply to these. The Act also recommends the voluntary adoption of codes of conduct which are based on the regulations for high-risk AI systems but can also go beyond them.

The above selection shows that classifying AI systems into the individual risk categories is only possible at a systematic level. Particularly for high-risk systems there are strict requirements and documentation obligations that mean that information needs to be obtained and documented in a structured way.

Alongside the above systems there are also specific requirements for what the legislation refers to as General Purpose AI (GPAI). The final definition of such systems has not yet been published, but generally they include AI models that have been trained through “self-supervised learning” on large volumes of data for a range of different purposes rather than one specific task. They include, for example, large language models such as OpenAI’s GPT-3 and GPT-4 used in ChatGPT and elsewhere, or DALL-E, also developed by OpenAI, and Bard developed by Google.

Additional requirements apply to such models with respect to transparency, compliance with copyright requirements and the publication of a “detailed summary” of the data used to train the models. What exactly is meant by a detailed summary remains to be seen.

If such GPAI systems have been built with large computing power (the EU mentions a limit of 1025 FLOPs (floating point operations per second), there are further requirements regarding the evaluation of the models, the requirement for analysis of systemic risks associated with the models and the obligation to document and report incidents involving such GPAIs to the European Commission.

Step 3: Create clear timetables

Even if it is unclear whether the timetable for the entry into force of the AI Act can be met, it makes sense to carry out an initial risk assessment of the systems in use in the company now to be prepared for the legislation entering into force and, if applicable, to implement measures already to meet the requirements of the Act. This is particularly recommended for complex organizations or those with a large number of AI applications. Preparing early will avoid complications later and enable the company to issue rules that apply when developing or buying AI applications in good time. In particular, implementing changes that require an intervention in applications that have already been implemented and used will be complex and time consuming and require detailed discussions with the relevant operating units. Large-scale jobs announced shortly before the deadline can quickly cause dissatisfaction and annoyance. Clear timetables and instructions will make it easier to prepare the work.

Already various bodies such as the European standards organizations CEN and CENELEC, as well as ISO and IEC and various industry bodies are working on standards and best practice guidelines relating to the AI Act. In addition, the European Commission’s EU AI Pact appeals to companies to implement the requirements already, help to shape best practice and exchange ideas on the AI Act with other companies affected by it.

Through its membership of many of these bodies, EY will be happy to support you in understanding the requirements better and assist you in implementing them.

After entry into force: implementing, monitoring, developing

When the measures discussed above have been implemented, you are prepared for the entry into force of the AI Act. However, the work is not completed at this point. New AI implementations have to be continually monitored and new applications need to be developed and brought under the established processes and standards. In addition, the process needs to be adapted to the expected regular amendments to the legislation. Continual training and education of staff should also not be forgotten. Channels to provide advice and for complaints also have to be established and maintained.

To continually monitor new software and applications we recommend establishing a system of automatic controls covering new software and their installations. If you are installing a software that may possibly fall under the regulations of the AI Act, approval workflows could for example be sent from such a system to managers or specially trained staff. This makes it possible to review AI use in advance and subsequently track its actual deployment in the system. In addition, information or surveys can be automatically sent to users, or online training on the restrictions to be aware of when using the software could be automatically initiated.

It is important not just to rely on a rule- and controls-based approach in the company, but create a culture through training and communication that takes account of the possible risks and dangers when using AI systems and works towards minimizing or mitigating them altogether. Misunderstandings about the reliability, a lack of transparency or even unintentional discrimination by algorithms are a major risk. Responsible use of AI offers the opportunity to use better, more secure and higher capability models and so gain a competitive advantage on the market.

With a well-designed system of controls, many of the requirements of the AI Act can be met and documented through the measures discussed above or similar measures. In addition, to review the effectiveness of controls, cases can be drawn from such a system to carry out a risk-based audit efficiently. This enables you to prepare your company well for external audits of compliance with the AI Act, which could well become a USP compared to your competitors, provided it is put in place early.

Summary

Does your company use AI? At this point many people think of self-driving delivery vehicles or autonomous maintenance robots and intuitively answer no. But let’s ask the question in a different way: Does your marketing department use a system to send personalized advertising to customers?

What models do you use in your sales department to produce sales forecasts? How exactly does your HR department pre-filter job applications? All of these are potential areas where AI can be used and which will be regulated by the European Union’s AI Act in the near future.

Related articles

Switzerland is leading the AI transformation as it unfolds in Europe across sectors and countries – but the journey is far from over.

Five generative AI initiatives leaders should pursue now

Learn how to move beyond quick efficiency gains to a cohesive AI strategy that maximizes your growth potential in a fast-changing space.

How GenAI is reshaping private equity investment strategy

A balanced approach to investment strategy is needed to defend against GenAI disruption while also driving portfolio performance. Learn more.