EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

Tax controversy update vol. 9 - Discussion on DCF - Part 2

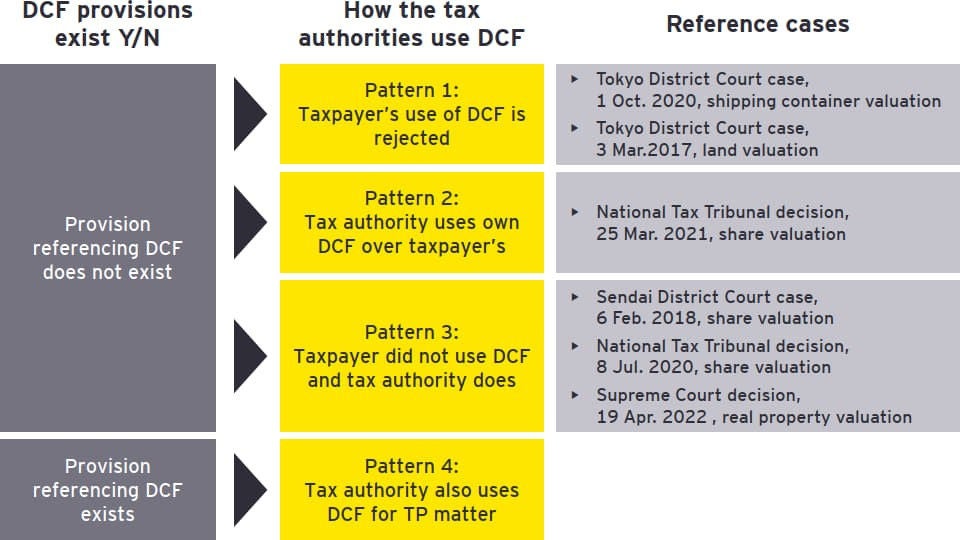

This issue continues the discussion on DCF (Discounted Cash Flow) which took place in the previous two issues. We will now take the opportunity to delve further into Patterns 3 and 4.

Pattern 3 refers to cases in which the tax authorities actively use the DCF method when the taxpayer used a method other than DCF to value assets.

In a Sendai District Court case dated 5 February 2018, the courts issued an order for the secondary tax liability obligation related to the remittance of delinquent taxes of the original taxpayer was in dispute.

The market value of the shares received by the secondary taxpayer from the delinquent company was the primary issue, and the tax authorities relied on DCF to perform the valuation.

As there are no provisions in the Basic Property Valuation Directive that stipulate the need to evaluate the market value of assets transferred without consideration, it was determined that there is similarly no need to use the Directive to determine the value of the shares in question.

In a separate case from the National Tax Tribunal dated 8 July 2020, the market value of shares without trading exchange values was the topic at hand. The taxpayer valued the shares by using comparative values of similar companies as stipulated in the Property Directive, but the tax authorities determined this methodology was highly inapplicable and instead performed the valuation themselves using DCF. Although the Property Directive clearly stipulates the valuation method for such assets, the tax authorities used Paragraph 6 of the general provisions from the Directive to claim the treatment used in this case was not appropriate.

A recent Supreme Court decision from 19 Apr. 2022 regarding a real property valuation is now a well-known case also due to its use of the aforementioned Paragraph 6. The tax authorities again used DCF to value the real property in this case.

As we discussed in the previous issue, DCF tends to be easier to use for the tax authorities when there are no clearly codified provisions of valuation methodologies to rely on. A taxpayer should be wary that even if a valuation is performed in accordance with a set of regulations or directives, there still exists a possibility that it will be denied using a general provision such as Paragraph 6, and an even higher valuation amount will result due to the application of DCF.

In addition, if the taxpayer is using DCF as a reference for the sale price and not for tax purposes, the tax authorities may still claim that valuation to be a tax valuation.

In order to avoid this scenario, it is important to carefully filter which documents are submitted in a tax examination and to prepare a rationale for explaining why DCF was not used.

Finally, as mentioned at the top of Issue 7 of this series, Pattern 4 refers how DCF was approved under transfer pricing rules as a method available for calculating an arm’s length price of intangible assets. However, this is not to say that the use of DCF by a taxpayer was unconditionally accepted. The rules accepting DCF also included a stipulation that the tax authorities could correct the transaction value after the fact in the event there was a discrepancy between the forecasted earnings and actual earnings when DCF was used. This fact is likely to be a point of contention for newer disputes over the appropriateness of transaction prices for intangible assets, and something taxpayers should especially be vigilant of. Our next issue will cover this point, as well as the impact the 2019 transfer pricing rule changes have had on tax examination procedures.

Contact

EY Tax controversy team

Direct to your inbox

Stay up to date with our newsletter.

Tax

Our tax professionals offer services across all tax disciplines to help you thrive in this era of rapid change.