EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

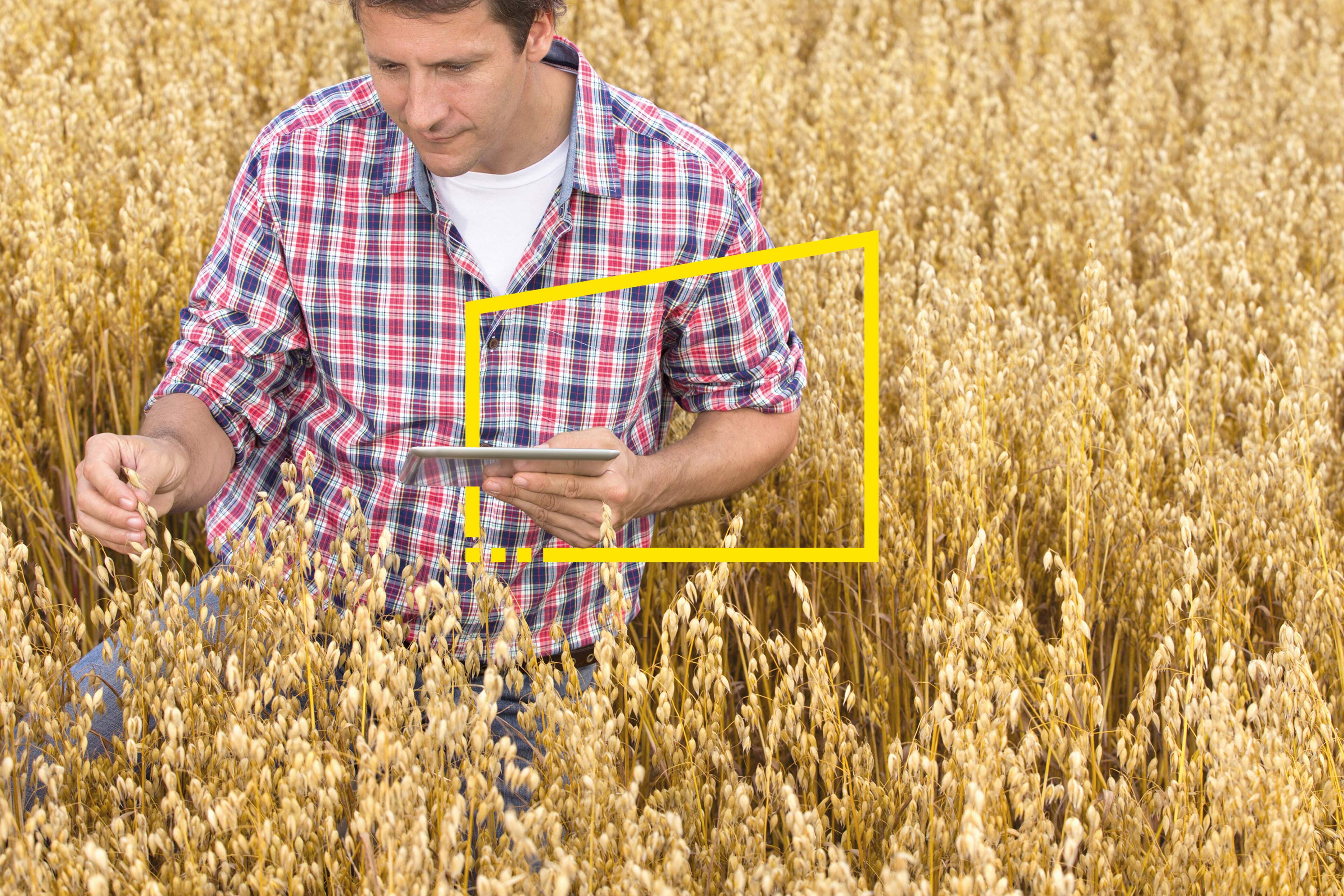

With the right focus, digital technology can help lift millions of smallholder farmers out of poverty.

Doubling the productivity of small-scale food producers features prominently in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with good reason. As concerns rise over access to food, it’s worth remembering that smallholder farmers and their families make up three quarters of the world’s hungry and undernourished. Despite the many barriers they face, these farmers are responsible for more than half of the food calories produced globally. And compared with other sectors, the World Bank has posited that growth in agriculture is up to four times more effective in reducing poverty.

The actual and potential contribution of smallholder farmers has arguably been grossly undervalued to date. However, this is changing as recognition grows of:

- The challenges involved in producing more food on less land, using fewer resources

- The fact that in Africa and Asia, where the major increases in population are expected to happen, 80% of the land farmed and food produced is by smallholder farmers

- The ripple effect on sustainable development when smallholders (the majority of whom are women) can build a life beyond subsistence and channel their incomes toward the health of their families and communities

Particularly as demand for food increases, and the challenges affecting the world’s poorest farmers rise with the threat of climate change, spreading the benefits of digital agriculture is not just an urgent need, but good sense. Digital innovation offers the means for smallholder farmers to take their rightful place at the forefront of a sustainable agriculture revolution, empowering them with the tools and knowledge to increase their efficiency, yields and incomes to previously unattainable levels.

As highlighted in a new report from EY and the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA), digital innovation is already playing a major role across all parts of the agribusiness value chain; however, there remains a great deal more to be done to realize its full potential. With reference to leading examples across Africa and Asia, the report shines a light on the hallmarks of successful digital services and offers simple, practical frameworks for helping plot a clearer path to scale.

1. Think systemically

As well as considering how their products and services interact with others, digital innovators should also reflect on the “non-digital” dependencies and ramifications of their solutions. While digital is great at facilitation, the practical challenges of making something happen out in the “real world” can be fraught with complexity. (By way of an analogy, designing a ride-hailing app is one thing; having the cars, drivers and roads to actually get people where they want to go is quite another. So, too, are the legal and regulatory issues that such an innovation can raise.)

Framing the agricultural value chain as a complex adaptive system reminds innovators not to design services in isolation. It reminds them of the critical need to develop a deep understanding of market conditions, of the motivations of different actors — including brokers, field agents and aggregators — and how technology can serve and unite those interests.

It also supports and encourages investment of “patient capital” on the understanding that success will take more than a smart plan and disciplined execution. It will likely involve a process of evolution and course correction, taking time to listen and observe carefully how the system reacts at each stage of development, and adapting and iterating accordingly.

2. Recognize and respond to gaps in provision

Improving availability and affordability of quality agricultural inputs, awareness of improved farming practices and access to markets have been traditional focus areas for sustainable agriculture — and are therefore relatively mature. Conversely, the full potential of technologies, such as the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to better guide planting and harvesting activities, and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms to enable more effective farm management, has yet to be realized.

While logistics have already been disrupted to an extent (e.g., driving more effective crop collection and storage), there are still gaps in the provision of broader transportation services, as well as technologies that drive greater transparency across the supply chain. The latter, especially, will be a key requisite to further integrating smallholder farmers into global supply chains and looks likely to become the next major focus for disruption.

3. Maintain focus on commercial viability

Impact metrics are, of course, important, but without an equally rigorous focus on cost and scalability, digitally enabled services and business models will find it difficult to become truly self-sustaining. The business sustainability review scorecard methodology contained within the report provides digital innovators with a practical set of questions to help them evaluate the effectiveness of their service offering.

It does so by encouraging assessment of current and potential impact through three lenses: the impact of a particular service or initiative on smallholder farmers, particularly on their incomes, as well as wider benefits to society; the costs associated with establishing, supporting and expanding the service; and the potential for the service to scale and impact a greater number of smallholders.

Answers generate a score indicative of overall performance. 80%–100% indicates a service is impactful, cost effective and has significant reach, likely only having a couple of specific areas in need of attention to maintain and grow meaningful impact. 60%–80% indicates the service is reasonably efficient and effective on the whole, but with multiple areas in need of more urgent attention. Less than 60% indicates multiple significant challenges that must be addressed to achieve significant scale and impact.

In the latter case, especially, a second framework in the report can help guide a more in-depth reappraisal of the service’s fitness for purpose.

4. Use purpose to prioritize development and diffusion of innovation

When innovators can clearly articulate their purpose — and when they can isolate the components of the agricultural value chain most critical to achieving it — they can focus more of their time and resources to development of digital services that will make a lasting and meaningful impact in these areas.

Using a simple two-step process, the agriculture value chain gap analysis framework in the report can help innovators evaluate priority areas for development. The first is to determine the extent to which improving the efficiency and effectiveness of this value chain component is critical to achieving the enterprise’s purpose or social mission. The second is to evaluate the current maturity and effectiveness of the digital service for realizing that improvement.

With answers to both ranked on a five-point scale, this analysis can support identification of mismatches between criticality and maturity that warrant special attention.

Conclusions

With two billion people around the world relying on agriculture for their lives and livelihoods, achieving multiple SDGs will be difficult, if not impossible, without helping smallholder farmers to thrive. Making sure that smallholder farming pays and offers a life beyond subsistence is essential, not only to future food security, but also to lifting millions of people out of poverty and giving them the agency to change their lives.

Digital innovation can empower smallholder farmers with the tools and knowledge to increase their efficiency, yields and incomes to previously unattainable levels. However, fulfilling that potential requires a mindful approach and systemic thinking to break through the vicious cycle of expensive credit, low productivity and lack of market connectivity that so often traps smallholders in subsistence.

Successful innovators treat the vast and complex agricultural value chain as a complex adaptive system. They recognize both the potential and the limitations of technology as an enabler of transparency and connectivity, understanding not only the value and importance of integrating multiple parts of the value chain, but also the dependencies on “real-world” people and infrastructure to establish and embed different ways of working.

Ultimately, innovation that only helps optimize one particular component of the value chain is destined to be limited in its impact. The greatest advances in food production and smallholder livelihoods will come when services and business models are designed from the ground up to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the value chain as a whole, and when due regard is paid to how these models can be scaled.

Summary

Digital innovation can empower smallholder farmers with the tools and knowledge to increase their efficiency, yields and incomes to previously unattainable levels. Fulfilling that potential requires a mindful approach and systemic thinking to break through the vicious cycle of expensive credit, low productivity and lack of market connectivity that so often traps smallholders in subsistence.

Related articles

Digital agriculture: enough to feed a rapidly growing world?

New technology gives the agricultural industry an opportunity to improve productivity. But only if it can share and use the data.

How EY can help

-

Through EY Ripples, EY people can help your early-stage impact enterprise improve resilience, productivity and capacity to scale sustainably. Learn more.

Read more