EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients.

How EY can Help

-

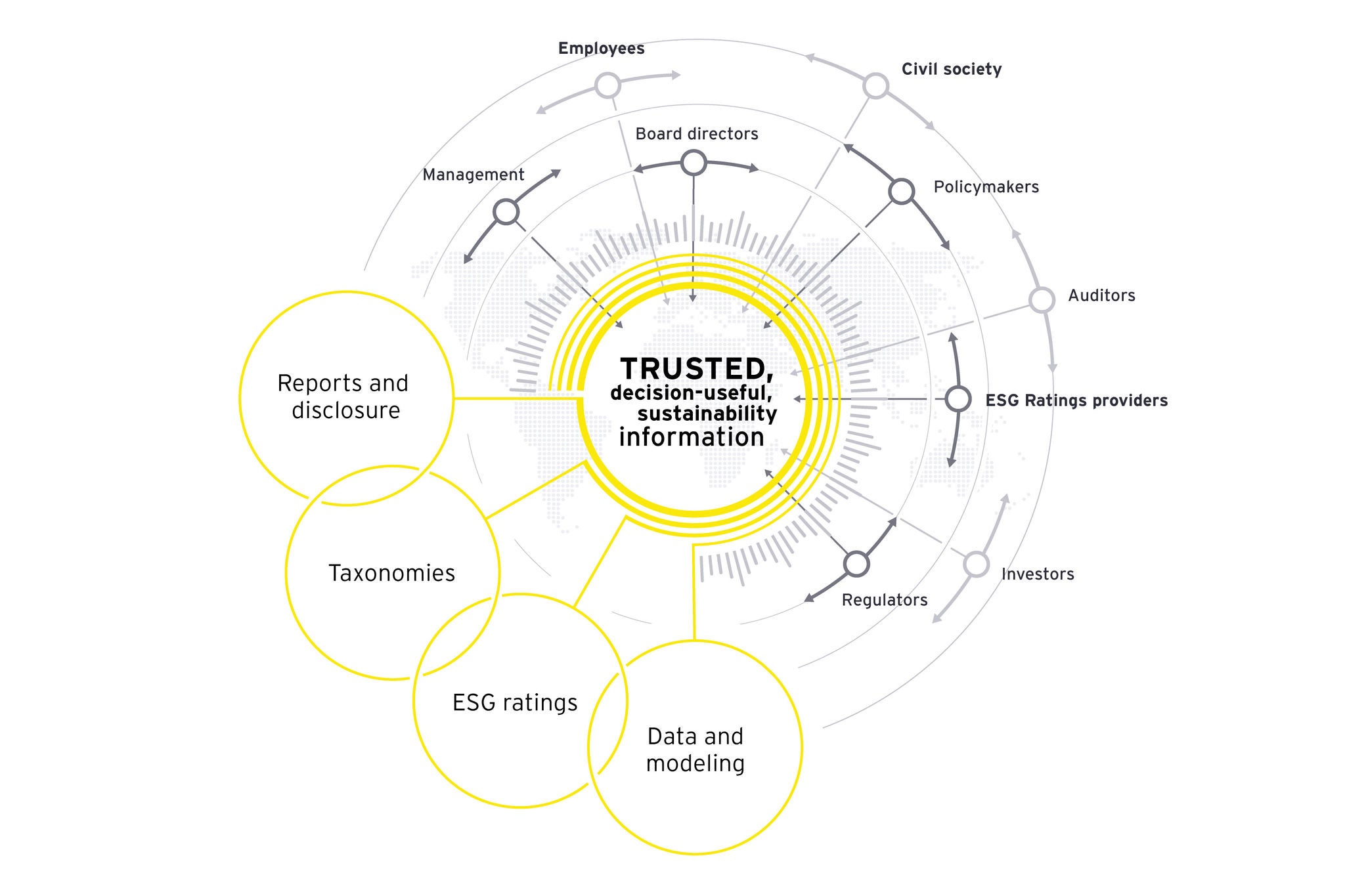

Sustainability and ESG services that help protect and create value for business, people, society and the world. Explore the depth and breadth of EY services and solutions.

Read more

5. Address the barriers faced by market participants in emerging countries

Emerging economies will account for a large majority of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Yet they have less resilience to be able to adapt to the impacts of climate change compared with some other markets. Due to their location, they are also likely to be more exposed to severe climate-related events.

The absence of comprehensive sustainability data in emerging economies suggests a need to lower barriers for market participants in these economies to disclose sustainability information. This is not to advocate different standards, which could be counterproductive. However, there should be more upskilling of technical assistance and engagement with emerging economies in the sustainability information ecosystem.

The international standard-setting work being done by the International Sustainability Standards Board may also benefit emerging countries, if they take the opportunity to adopt its standards into their own legal frameworks.

Next steps for companies, policymakers and investors

The ESG movement is still in its infancy – and much more work is needed to encourage open collaboration and trust-building. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to see that policymakers, standard-setters and regulators are already taking important steps to define and regulate the information investors seek. At the same time, market participants are collaborating in new ways to develop innovative reporting and data modeling solutions.

As these efforts move forward, it is critical for all stakeholders to engage in both the policy process as well as market-led initiatives and to make their voices heard. The actions we have explored are a contribution to these efforts and underscore why building alliances and forging collaboration is everybody’s business.