How the big tax reboot may impact Singapore

The country will need to review its tax rates and policies should the proposed global minimum tax on profits become a reality.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been working relentlessly toward achieving a global consensus on the design of a new international tax architecture. On 12 October 2020, the OECD released its reports on the blueprints of the two-pillar approach to address the tax challenges arising from digitalisation of the economy (that is, the BEPS 2.0 project). The Pillar One blueprint rethinks the profit allocation of large multinational enterprises (MNEs) among jurisdictions, expanding the taxing rights of market jurisdictions based on revised nexus rules. On the other hand, the Pillar Two blueprint proposes a global minimum tax for which profits ought to be taxed.

Getting a broad consensus on the proposals appeared bleakly possible until US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, made a similar call. The Biden tax proposals sought to, inter alia, enact a country-by-country minimum tax that aims to substantially curtail profit shifting and offshoring of assets by US MNEs, and deny tax deductions on related party payments to foreign corporations residing in a regime that has not implemented a strong minimum tax.

The need to pivot

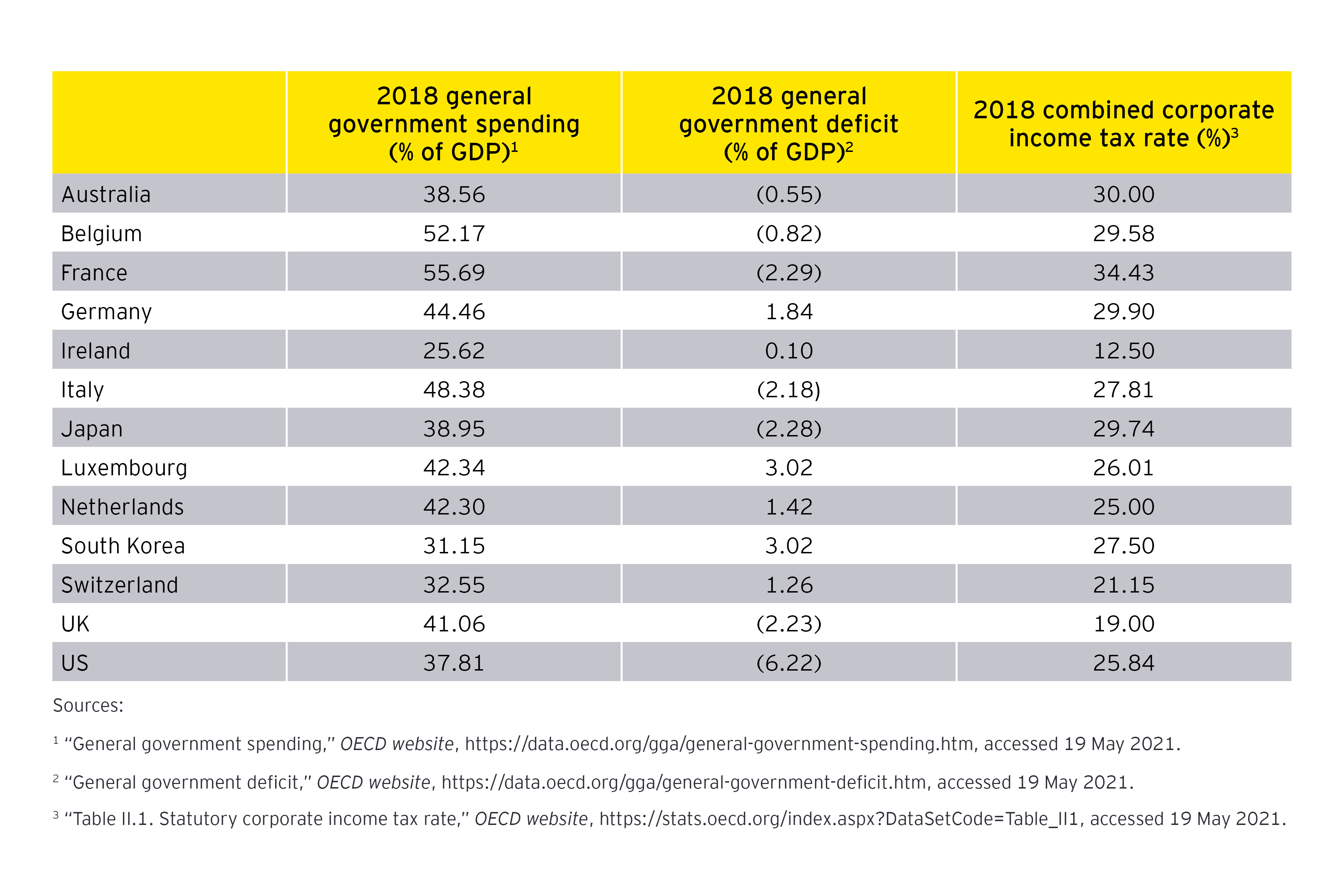

Generally, the corporate tax rate is reflective of a country’s level of government spending and budgetary position. The table below shows the general government spending and general government deficit as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in OECD countries as well as their combined corporate income tax rates in 2018.

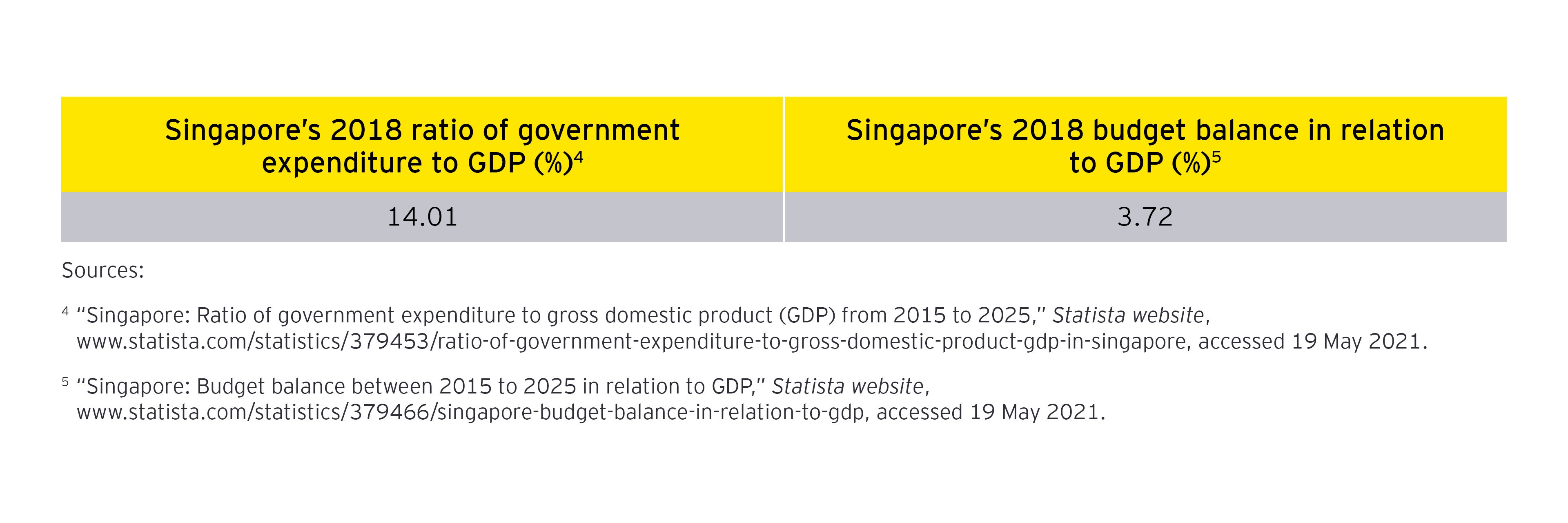

By comparison, Singapore has a relatively low corporate tax rate of 17%. Its ratio of government expenditure to GDP and budget balance in relation to GDP in 2018 are shown in the table below. The country has long maintained a strict fiscal discipline, allowing it to maintain a competitive corporate tax rate and use tax incentives as a tool to attract foreign direct investment for job creation.

The 2018 situation seen earlier is expected to have changed with increased government spending on COVID-19 economic stimuli and related support, and governments will invariably be compelled to look more keenly at driving revenues and tax rates.

For example, the Netherlands has canceled its planned reduction in corporate tax rate to 21.7% (from 25%) as of 1 January 2021, while Turkey, the UK and the US have unveiled plans for tax hikes. The prolonged road to recovery from this pandemic will engender tax hikes, new taxes, heightened tax enforcements and increased cross-border tax controversies. Understandingly, many OECD and G20 countries would support the global minimum tax proposal to prevent a race to the bottom: a tax competition many countries cannot afford.

Should this anticipated global minimum tax — or a tax reboot — materialise, it will inevitably limit Singapore’s choices in setting its own tax policies and indirectly challenge its sovereign rights. As a small city-state, Singapore will have to adapt and adjust its tax policies to fit into the new tax world.

BEPS 2.0 as a certainty

Under the current circumstances, BEPS 2.0 will be implemented in one form or another and the impact on the broader economy, investments, investment returns and jobs will remain to be seen.

Even with the appropriate economic substance, the global push for a minimum tax is likely to make paying zero or little taxes and parking profits in tax havens a thing of the past. MNEs must come to terms with this reality and brace themselves for a higher effective tax rate (ETR) wherever they operate.

In simple terms, the ETR is the percentage of earnings that a corporation pays in taxes. It drops when certain earnings are not taxable or taxed at a preferential tax rate, or when deductions are enhanced. Conversely, it rises with a denial of deductions or double taxation. As a result, the ETR can fluctuate year-on-year depending on the circumstances. In the BEPS 2.0 world, when the ETR falls below the agreed minimum tax rate, the “low-taxed profit” may consequently be picked up for tax elsewhere.

Some countries, such as Austria, India, South Korea and the US, have introduced some form of alternative minimum tax (AMT) in their tax regimes. AMT ensures that corporate earnings are subject to tax at a certain floor rate, and such a regime may help Singapore avoid any unintentional relinquishment of taxing rights when BEPS 2.0 is in place. The introduction of AMT could, however, increase the administrative burden on Singapore taxpayers. Simplifying the rules, such as aligning the ETR computation with that of the BEPS 2.0 proposal, will help with Singapore’s tax competitiveness.

The big tax reboot will transform the game for Singapore, where tax incentives have been instrumental to its investment promotion efforts. Having said that, Singapore’s long-standing merits in its institutions, infrastructure, labour market and financial and legal systems should continue to make it an attractive investment destination. As uncertainty looms around the world, may Singapore’s consistent performance and stable government policies keep this city-state shining as brightly as ever.

The author is Chester Wee, EY Asean International Corporate Tax Advisory Leader.

This article was first published in The Business Times on 12 May 2021.