Two-year project

Few are better placed to push this message. A former Vice-Chairman of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and a former Chief Accountant of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission, Mackintosh has more than 30 years’ experience of national and international accounting standard-setting under his belt.

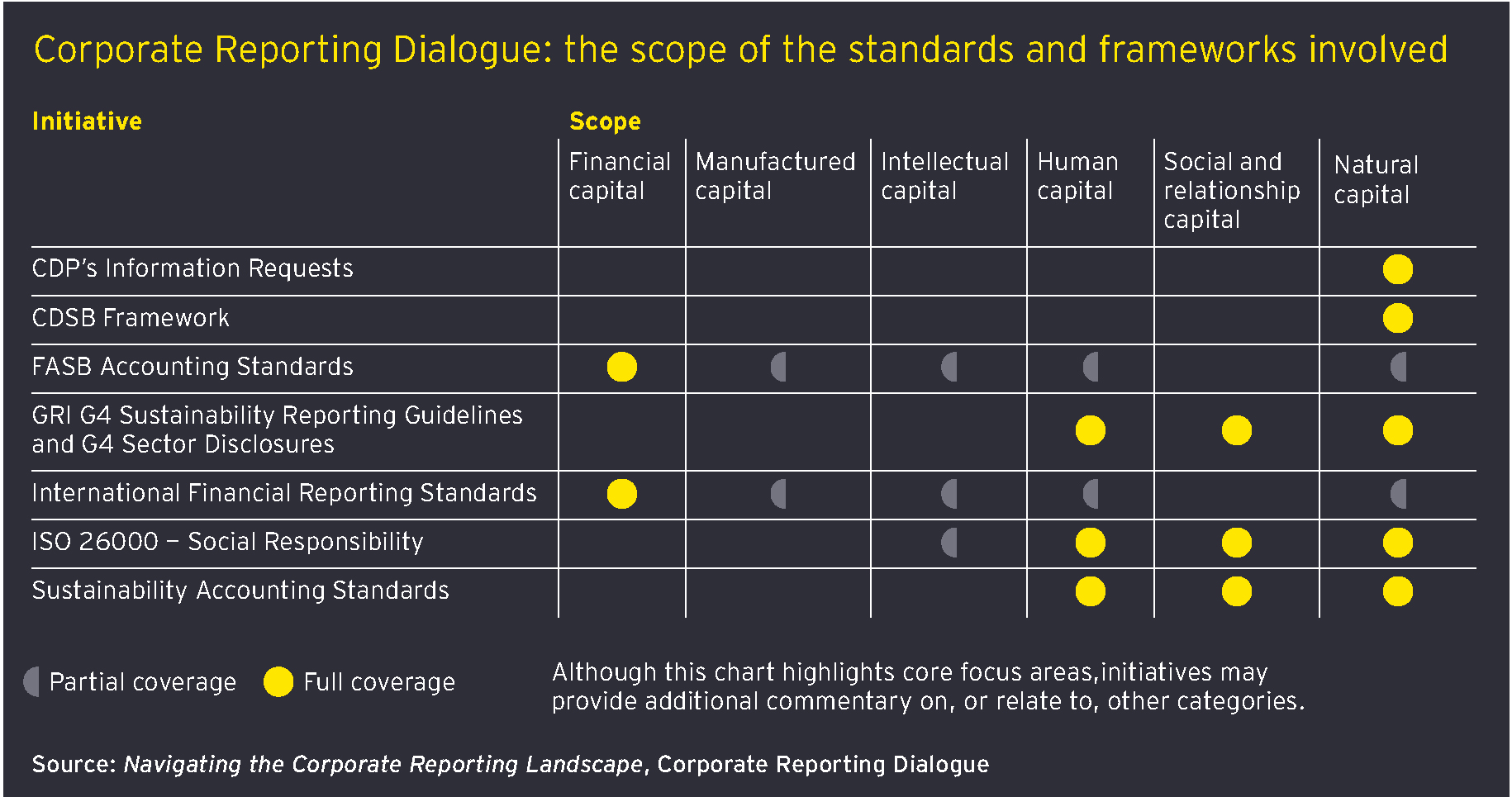

He is now leading a two-year project focused on driving better alignment in the corporate reporting landscape. CRD participants have committed to driving better alignment of sustainability reporting frameworks, as well as those that promote further integration between nonfinancial and financial reporting.

The project comes in two parts. “The first looks at the TCFD disclosure proposals and tries to map how they fit with existing frameworks and metrics, and we will be formally reporting on this in September this year,” Mackintosh explains. “The second is about standard setters and framework providers discussing what they are doing, finding out what is similar and what is different, and discovering how we can better align and rationalize these standards.” This latter part of the project will report in September 2020.

Mackintosh says the group is not difficult to chair. “They are positive, they are trying to work together. Yes, they have their own priorities and points of view, but we do meet to talk about common issues. All of this is done on the basis of consensus, and that is an achievement in itself.”

The process is not necessarily aimed at reaching an ultimate answer on alignment; rather, it is about preparing steps toward an ultimate answer. But is there a common thread that pulls the different standard setters and framework providers in the same direction? “Having to satisfy everyone is not an easy task, and there will have to be a bit of give and take if we are going to succeed,” Mackintosh acknowledges.

Even if the CRD does achieve agreement on the way forward at the end of the two-year project, it could still take time to implement any changes into actual regulation. Mackintosh points out that, globally, there is very little regulation related to the alignment of financial and nonfinancial information. Notable exceptions include the requirement for UK-incorporated companies to publish a strategic report in the annual report that covers a fair review of the company’s business and a description of the principal risks and uncertainties facing it, and the Australian Securities Exchange’s corporate governance guidelines, which require publicly-listed companies to disclose nonfinancial risk. “Even the IASB doesn’t have any regulatory powers [in this regard],” he adds.

This raises further questions. How should nonfinancial information be regulated, and by whom? Would regulators enforce a comparable framework on everyone? Helpfully, the IASB has a set of reporting standards that look at what else would be reported beyond financial information. And, while easy answers are elusive, Mackintosh says the debate is worth having, to get people thinking about why nonfinancial information is important.

Related article

It’s quite possible there will be some resistance. Every time there are changes, you always get the message that ‘you can’t do this, it’s too much.

Finding the fit

The CRD’s initial focus is on getting some order into the reporting of nonfinancial information and working out how it fits with financial information. “At that stage, you can start looking at an annual report that has this information in one document, encompassing both financial and nonfinancial information,” he says. “One complements the other.”

Another key issue for the CRD is materiality. “Companies should only report on things that are relevant to them, not just have a checklist of things to report on,” says Mackintosh. “It has to be relevant to the company itself, and that goes back to who you are reporting to. The IASB, for example, reports for providers of capital, whereas the Global Reporting Initiative would say it is reporting for society, so that’s a broader range of users.”

Another looming challenge is possible pushback from large corporates, which are already complaining of “reporting fatigue,” according to Mackintosh. “It’s quite possible there will be some resistance,” he says. “Every time there are changes, you always get the message that ‘you can’t do this, it’s too much’. And often, it can be legitimate. Standard setters do on occasion require things that aren’t very relevant.”

Forging consensus

In February 2019, CRD participants released a position paper on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – a blueprint of 17 targets devised by the United Nations to achieve a better and sustainable future for all – and the future of corporate reporting. The paper identifies how corporate reporting can illustrate which SDGs are relevant to a company’s business model, enabling both companies and investors to focus on those SDGs most likely to impact financial performance.

“It’s a good basis for beginning the debate,” says Mackintosh. “It’s a starting point for what could be reported, what is relevant and what cost benefits are related to SDGs.”

Nevertheless, there is criticism that things are not moving fast enough. “People are coming to us saying, ‘couldn’t you do something more quickly and with broader ramifications?’ That’s another challenge,” says Mackintosh.

So should there be a single global standard setter on corporate reporting that takes in both financial and nonfinancial reporting metrics? Mackintosh admits he is sympathetic to that view.

“You’ve got to have a dream, as the songwriter said. If you don’t have a dream, then how are you going to have a dream come true? In an ideal world, at an ideal time, yes, that is the way I would personally like to see things pan out.”

However, he says the CRD has deliberately not pushed such a “catch-all” solution because of concerns that it would deter people from joining in the dialogue. “I’m not trying to coerce people into things they don’t think are right, either for them or for the overall market,” says Mackintosh.

Moreover, any rationalization of standard setters could prove challenging to bring about. Many entities might be reluctant to be voluntarily subsumed into a larger organization.

“Change could come from the bottom up,” Mackintosh predicts. “Organizations might decide to merge if they have a proper look at each other and their goals. There have already been a couple of mergers that have narrowed down the market, and that makes taking additional steps toward convergence easier.”

The fact remains that many observers, both on the inside and the outside, are far from happy about the present situation and are asking why something can’t be done. Mackintosh believes the pressure from the market – from both funders and investors – will ultimately forge consensus, even if this falls short of full integration.

“But it’s not going to be simple,” he concludes. “These organizations have a rationale for what they have done and are not going to give that away unless they are assured that what comes next is better than the status quo.

The views of third parties set out in this article are not necessarily the views of the global EY organization or its member firms. Moreover, they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.

Summary

Ian Mackintosh, Chair of the Corporate Reporting Dialogue, explains why that organization has instigated a project to explore ways of driving better alignment of sustainability reporting frameworks, particularly those that integrate financial and nonfinancial information. This could eventually lead to changes in regulation, and even raises the prospect of a single global regulator for corporate reporting, but Mackintosh acknowledges that this is still a long way off. For now, the focus is on finding common ground between the bodies involved in the discussions.