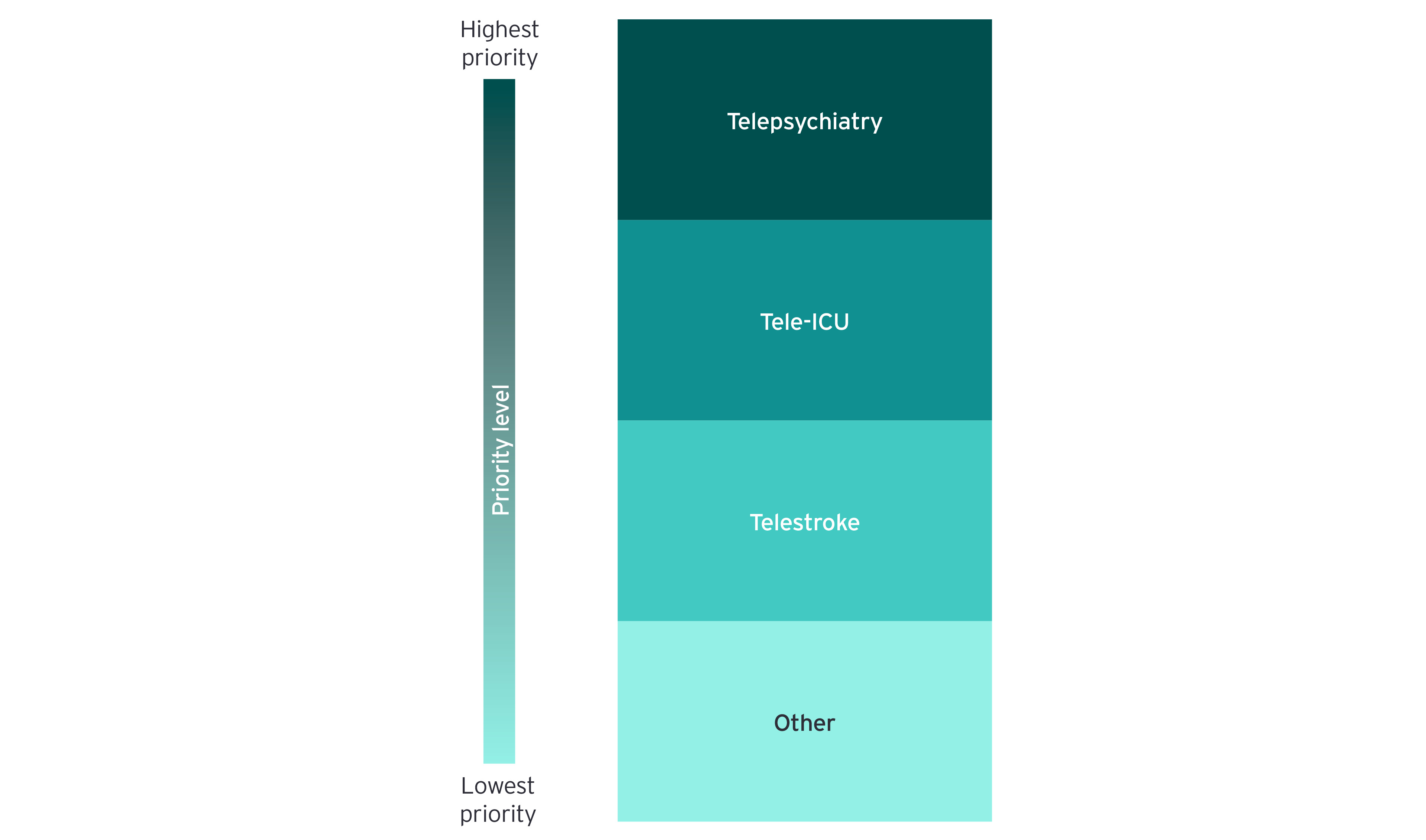

Teleneurology — particularly remote stroke care — is a more mature application of acute care telemedicine and has benefited from provider investment over the last few years. Going forward, the spend on remote stroke consultations is likely to increase, but at a slower pace than that for telepsychiatry, although the demand for teleneurology remains strong. According to a CIO, “Telestroke is a very well evolved model. I could see growth continuing there. In telepsych, there are just phenomenal opportunities because it’s a massively unmet need within our health care system.”

Health systems are also increasingly centralizing teams of providers in a common location or command center to coordinate care for critical patients in ICU settings. These tele-ICU capabilities also enable rural systems that lack specialists to holistically care for patients in cost-effective and sustainable ways.

Providers have especially utilized tele-ICU capabilities during the COVID-19 outbreak to limit the infection exposure and optimize the use of scarce personal protective equipment resources, and to address a strained shortage of critical care physicians. Almost all states in the US are expected to experience a shortage of intensivists in the future, and tele-ICU models are a possible solution for relieving those stressors.⁷

The importance of clinician-to-clinician telemedicine models in acute care settings is amplified for health systems and hospitals in underserved or rural geographies (e.g., critical access hospitals). However, decision-makers at larger health systems also see value in expanding clinician-to-clinician telemedicine access given the complexity of care needs and to bolster clinical capacity at adjacent, understaffed sites within their system.

Business model evolution

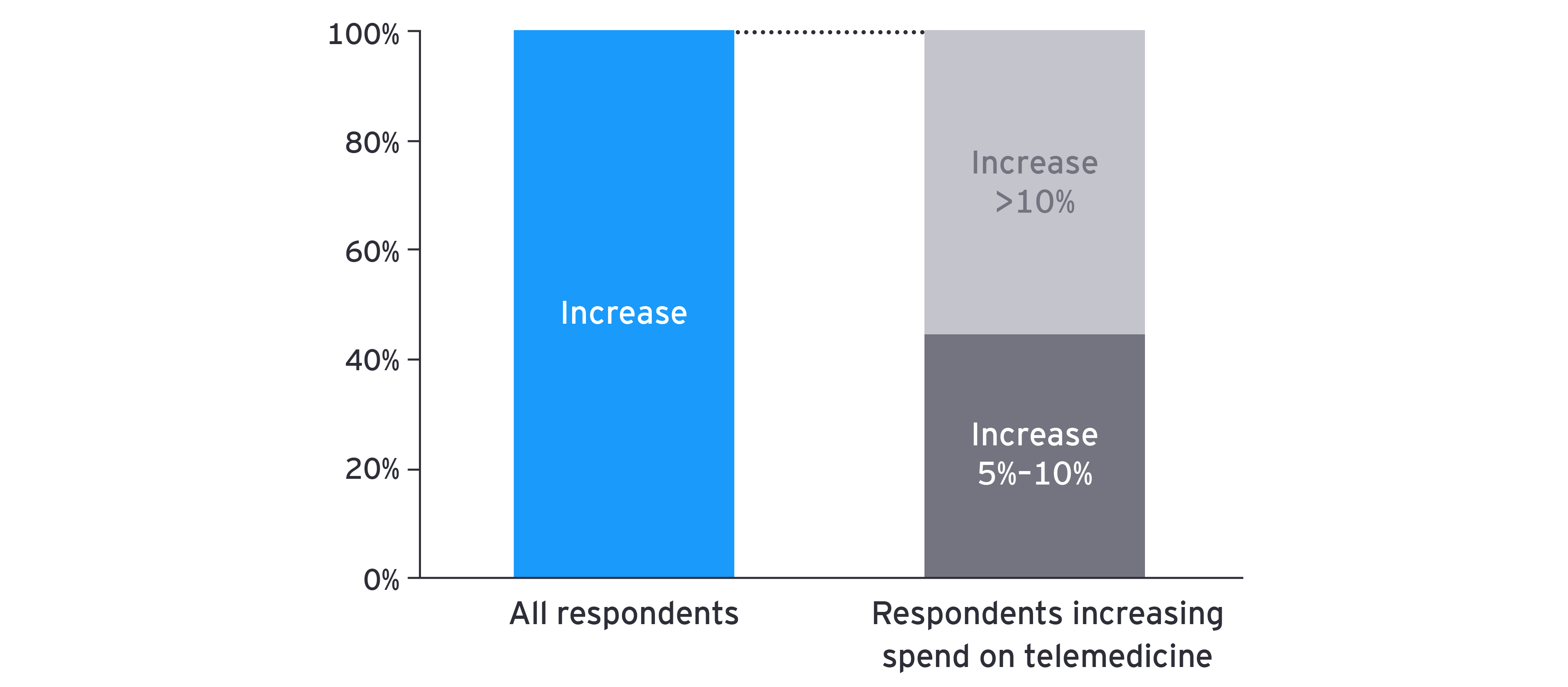

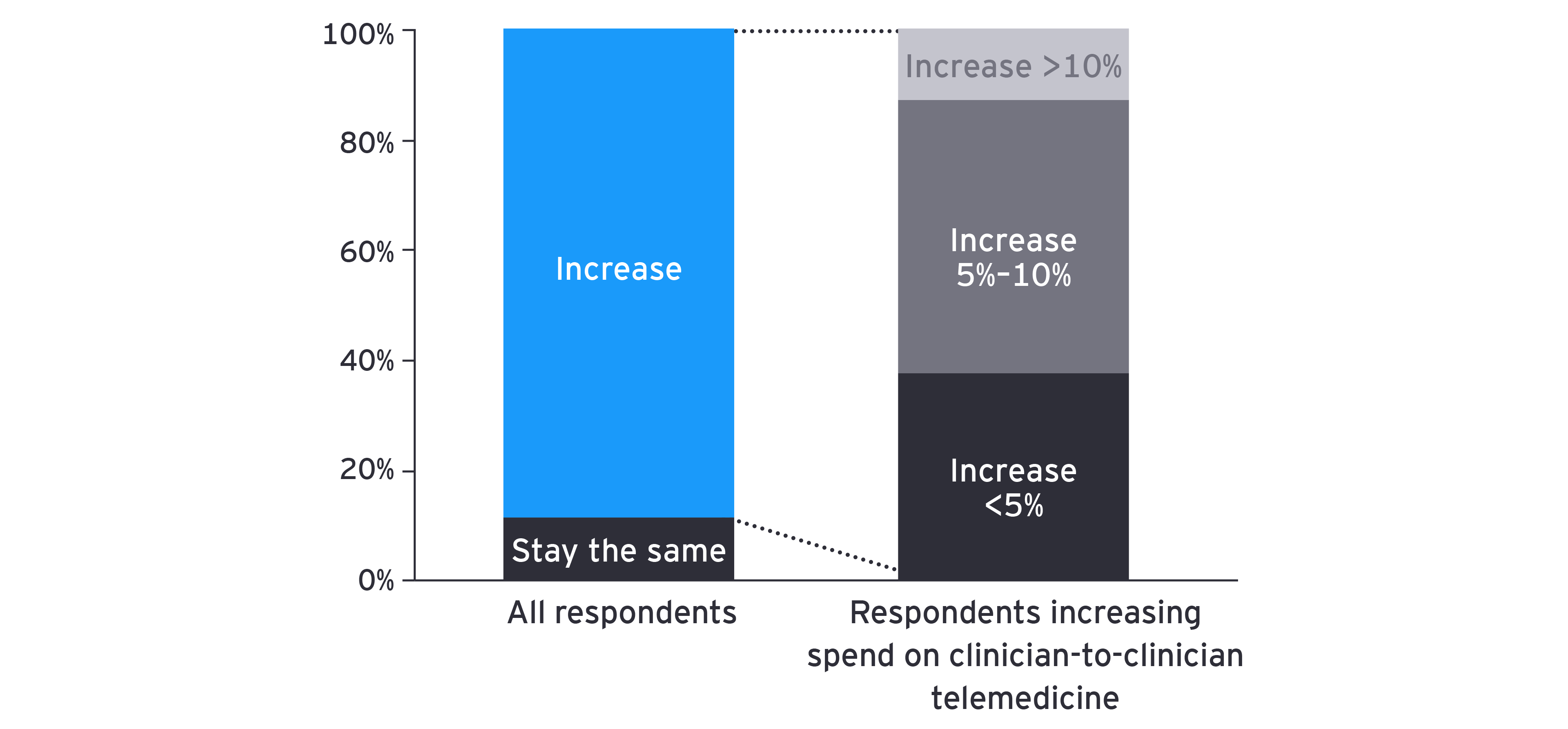

While clinician-to-clinician telemedicine in acute care settings might not see a “hockey-stick” adoption — as may be the case for other telemedicine capabilities in the care continuum, such as virtual primary care — clinician-to-clinician models are resilient, and health system decision-makers indicate an interest in the continued investment in these technologies.

This resiliency stems from the technology’s demonstrable ROI and scalability in expanding access to specialist care. In some instances, larger health systems with access to specialists (e.g., academic medical centers) have invested in capabilities internally and can provide services to other hospitals.

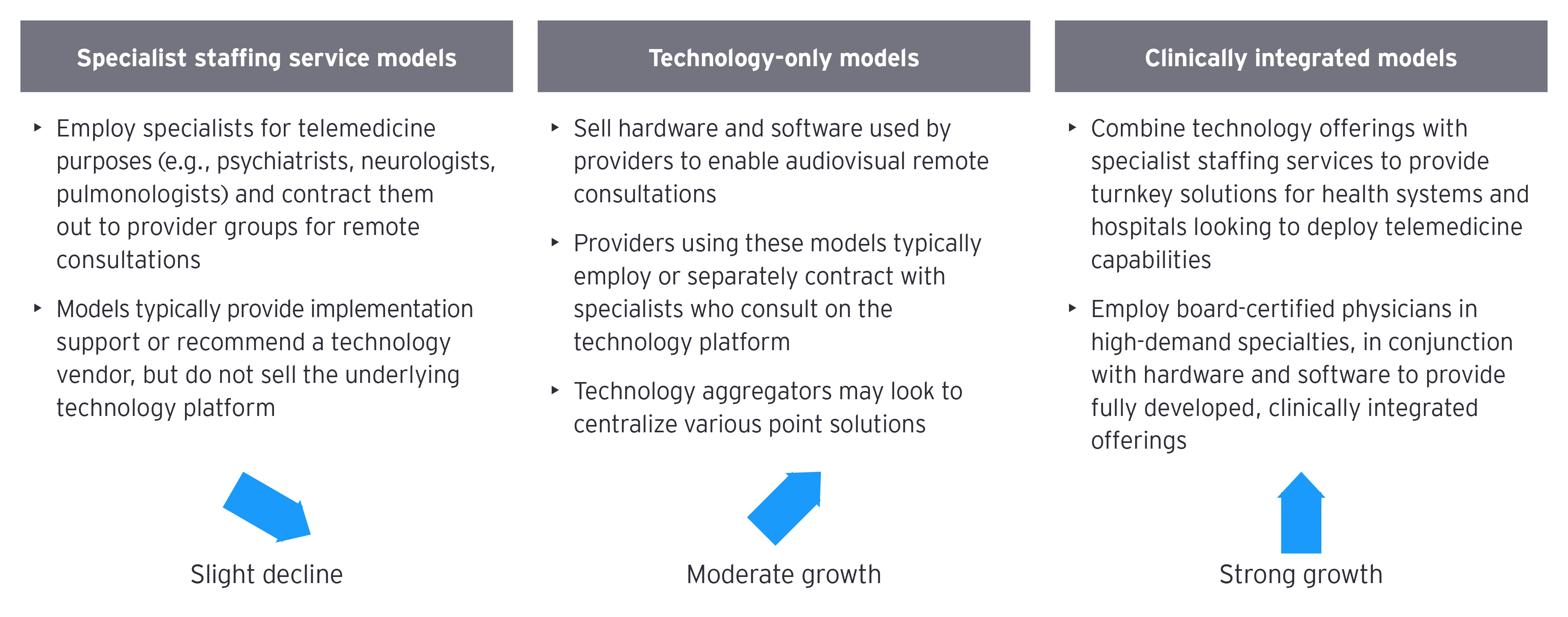

In addition to in-house models, a variety of third-party business models exist to support health systems and hospitals in their deployment of clinician-to-clinician telemedicine capabilities. Most prominent among these are three models: specialist staffing services; technology-only models; and clinically integrated, full suite offerings (technology and staffing [Figure 5]).